St. Anne Woods and Wetlands (SAWW) is a 155-acre conservation area along the Ohio River that features wetlands, old-growth and secondary forests, and grasslands.

NKU REFS partners with the Campbell County Conservation District (CCCD) to support research, education, outreach programs, and conservation efforts in this unique habitat.

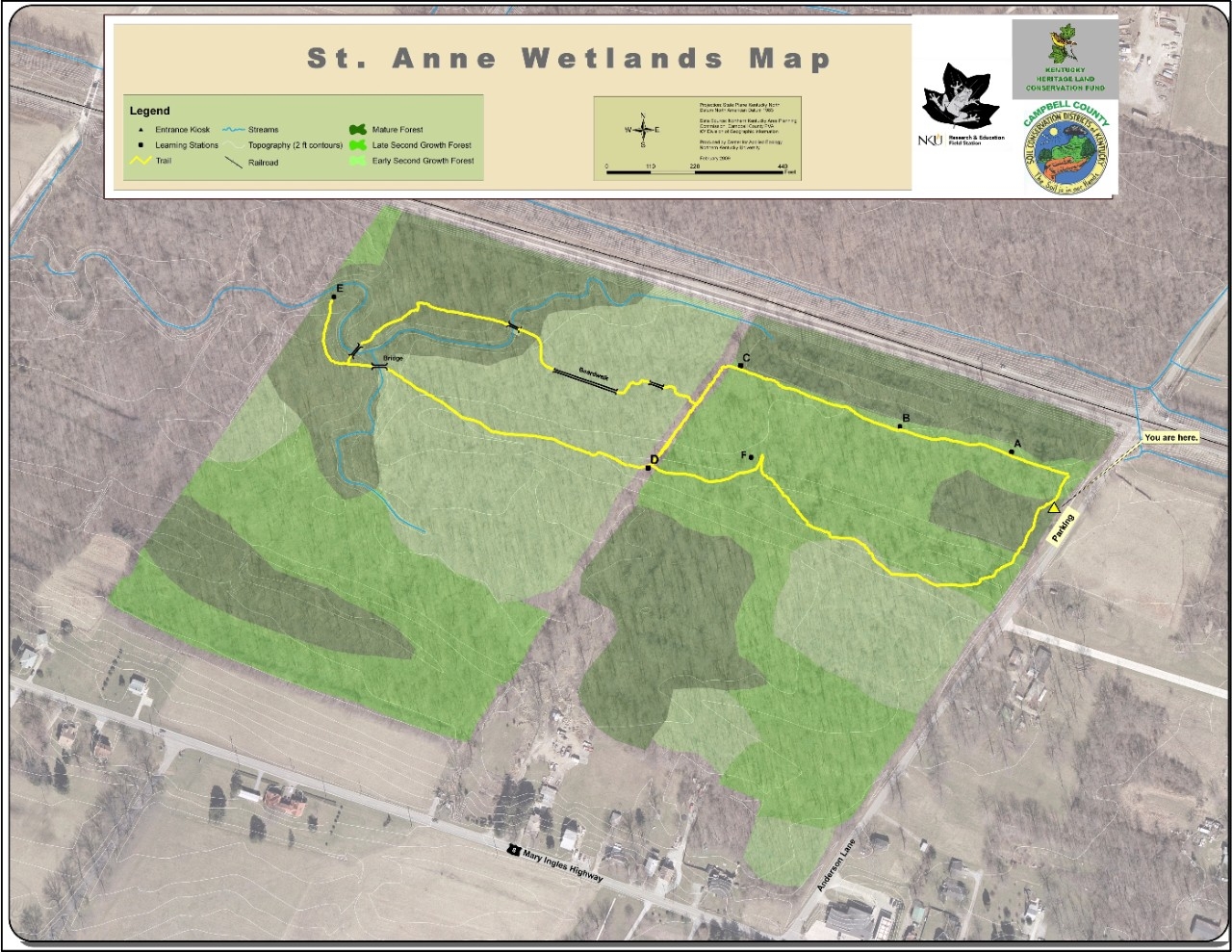

A public trail system in the south wetlands features six interpretive kiosks and a main trailhead kiosk, offering visitors a chance to learn about and explore this natural area.

St. Anne Woods and Wetlands (SAWW) is a 155-acre (63 ha) conservation easement along the Ohio River that includes open and closed canopy wetlands, upland old-growth and secondary forests, and associated grasslands.

Renowned ecologist Dr. E. Lucy Braun, the first female president of the Ecological Society of America and one of the first female professors at the University of Cincinnati, studied these forests - then known as “Melbourne Woods” - over 100 years ago. Since then, the area has remained an important site for ecological research and education.

In 2008, a Community Partners Grant from Northern Kentucky University (NKU) brought together local universities, agencies, industry, community members, and the Sisters of Divine Providence to create a trail system and expand opportunities for research and environmental education. These programs have since served thousands of students (P–12 through university), educators, and community groups across Northern Kentucky and Greater Cincinnati.

The Sisters of Divine Providence preserved the land until 2013, when the Campbell County Conservation District (CCCD) acquired it with support from the Kentucky Heritage Land Conservation Fund. The property is now permanently protected under a conservation easement held by the Commonwealth of Kentucky. NKU’s Research and Education Field Station (REFS) maintains a memorandum of understanding with the CCCD, supporting continued use of the site for research, education, and outreach.

REFS also carries out the conservation efforts to maintain the trails and kiosks on site. In 2021, REFS and NKU students and faculty collaborated with the CCCD and the community to build a set of boardwalks on the trails, which help prevent damage to the wetlands during the wettest portions of each season.

Today, the public can explore a trail system in the south wetlands, featuring six interpretive kiosks (A–F) along the path in addition to a main kiosk at the trailhead.

The trail leads past a depression forest and then follows a low ridge to the end of the path, located 2,150 feet from this point. The depression forest (learning stations A, B, and C) consists of tree species that can tolerate seasonal flooding, e.g. pin oak, cottonwood, sycamore, green ash, and red maple.

Upon reaching the low ridge (D), the trail either proceeds to the right or to the left. The left tail forms a loop to return to the entrance, while stopping at station (F) where wetland restoration took place. The trail to the right from (D) proceeds through an area where old-growth upland forest was cleared to allow the cultivation of crops and pasturing of livestock. An early second-growth forest has developed in the decades since the farmland was abandoned. The woodland contains such trees as sassafras, black cherry, and tulip poplar.

The right trail from (D) bridges a creek and enters a grove of beech trees (E). The homesteader spared this remnant of the original forest to provide beechnuts for foraging hogs and serve as a source of lumber and firewood. The trail ends in the beech grove and visitors can either return to the entrance by retracing their steps or crossing the second bridge and taking the northern circuit trail across another bridge and two boardwalks through the depression forest to rejoin the initial trail at learning station (C).

A Northern Kentucky University (NKU) Community Partnership Grant supported trail construction and its signage. Now research and educational programs are run through the NKU REFS.

Map of the trails for the St. Anne Wetlands south.

A forest ecosystem is comprised of many layers: canopy, understory, and forest floor. The understory is the layer of a forest made up of shrubs as well as small trees growing to reach the canopy layer. Less light is able to reach this lower layer, so understory plants must be able to complete their life cycle in the shade of the forest сапору.

Notice the difference in plant composition between where you're standing and the wetland, the depressed area behind this sign. Two feet in elevation makes a big difference! The roots of the plant species in the higher area around this sign would suffocate under standing water, while the roots in the wetland plant species are adapted to survive part of the year under water. Understory shrubs prefer the drier, well-drained areas outside of the wetland. Shrubs around this sign include Spicebush, Amur Honeysuckle, and Pawpaw.

The first shrub just to the left of this sign is Spicebush (Lindera benzoin), a shrub known for its spicy aroma. Clusters of small greenish-yellow flowers bloom along the branches in early spring before the leaves emerge. Red berries attract birds in late summer, and thick, light Green leaves turn yellow in autumn.

The next shrub to the left of this sign is Amur Honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii), the most common shrub in this understory. It is an invasive species from Asia imported to control erosion and to serve as an ornamental shrub. It grows fast, forms dense thickets with long-lasting foliage, and native plants have difficulty competing in these areas. Amur Honeysuckle's sweet, white flowers bloom from mid-spring to early summer. The fruit is a red berry that is poisonous to humans but is eaten by birds, which spread the seeds in their droppings.

Finally, 15 feet to the left of this sign are Pawpaws (Asimina triloba), clustered shrubs of large, dark green leaves with a scent similar to a green bell pepper. Spring brings flowers with petals that vary from purple to red-brown. The edible fruit is easily seen in autumn when the leaves turn a rusty yellow. Bark of the Pawpaw is dark brown and blotched with gray spots.

While the wetland behind this sign lacks understory shrubs, it does support large trees that form a canopy. These species include the Cottonwood (Populus deltoides) with its deeply furrowed bark and the American Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) with whitish, peeling bark. These species are both native to this region and are known for their hydrophilic (water-loving) tendencies. In contrast, the native tulip Poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), a species not found in floodplains, is absent from the wetland but is common in the area at a slightly higher elevation on the opposite side of the trail.

The tree canopy not only serves as a habitat and foraging environment for many species, but it also creates conditions that contribute to the great diversity of wildlife in the wetland. The architecture of these trees consists of woody branches supporting a canopy of leaf foliage stretching across openings to fill any gaps and trap as much light as possible. The tops of the trees can range in height from about 15 feet to 50 feet off the ground. This variation in height alone creates a diversity of habitats for a range of bird and mammal species. For example, Cardinals and Mockingbirds are found in the lower canopy trees, while Woodpeckers and Nuthatches are more common in the mid-canopy, and Warblers are in the highest part of the canopy. In addition to birds, the Canopy also provides habitat for Squirrels, Raccoons, Opossums, and a variety of other animals. The canopy captures sunlight and intercepts wind and precipitation, thereby buffering climatic extremes in the understory and forest floor microhabitats.

The dominant tree in this part of the wetland is the Pin Oak (Quercus palustris), a tree that is adapted to be under water longer than any other tree species in this region. Notice that the water marks on the tree trunks are deeper than those seen on the trees elsewhere, an indication that this area of the depression forest is the deepest and slowest to drain.

The frequent flooding of the wetland sustains an abundant community of amphibians. The watery ephemeral refuges serve as a breeding ground for several species of frogs, toads, and salamanders. These animals characteristically have and must maintain a moist skin, which can be used as a breathing surface, like an inverted lung. In fact, some of the salamander species (Family Plethodonidae) found in the nearby leaf litter or under rocks and logs in the area have lost their lungs completely and use their skin as their exclusive respiratory organ. Two amphibians inhabiting this wetland are of special interest, the Jefferson's Salamander and the Wood Frog.

Jefferson's Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) is a type of mole salamander that is active above ground primarily during early spring (February - March) breeding season, and occasionally during heavy nighttime summer showers. During these breeding periods, a male will court a female by performing a dance of sorts with a good deal of body contact to lead her to a particular breeding location on the bottom of the pool. The young remain in the water with gills until they metamorph into adult salamanders. As salamanders go, these amphibians are robust with a rounded head and a thick body with short legs. They are brown to slate gray in color with light blue flecks along the sides of their bodies. They consume insects, earthworms, and other invertebrates.

The Wood Frog (Lithobates sylvaticus) is a rare species to be found in Northern Kentucky. While relatively abundant across the River in Ohio, this wetland holds one of the few populations of this species in the Northern Kentucky region. Like the Jefferson's Salamander, the Wood Frog is one of the first amphibians to breed in the spring, sometimes while there is still ice on the water. They are an explosive breeder, which means that there is a very small window of time (one to two weeks) in which males and females come together in the wetlands to lay clutches of eggs. The call of the male Wood Frog sounds like squabbling ducks, yet this is enough to attract the females to the breeding location. Tadpoles remain in the pond until late spring when they metamorph into small froglets. These frogs are brown to bronze in color with a black mask around the eyes. They inhabit the forest floor of undisturbed deciduous woodlands and are voracious consumers of mosquitoes and other insects. These frogs remain in the leaf litter throughout winter and have the amazing capacity to be frozen as solid as an ice cube, only to thaw in the spring and head for the nearest breeding water.

After this sign, the trail turns left. From there, you can either:

The strip of open land along which this sign is located is a right-of-way for a sewer line. As you look up and down the right-of-way, you will see that you are standing on a slightly elevated portion of this property. The forest vegetation in the vicinity of this sign consists of tree species that are different than those growing in the lower, wetter areas.

A Beech forest covered this site in the early 1800s. Among local tree species, the American Beech (Fagus grandifolia) is best adapted to growing in moderately drained soil. An early owner cut down the original Beech forest in order to establish a farm field in this area.

The farm field was abandoned in the mid-1900s, and soon the site became covered by pioneer tree species such as Sassafras (Sassafras albidum), Black Cherry (Prunus serotina), and Tulip Poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) growing from seeds carried here by wind and birds. Beechnuts were likely carried into the field by mammals, but Beeches did not thrive in the sunny, dry area.

Sassafras, Black Cherry, and Tulip Poplar continue to dominate this woodland. These sun-loving species, however, do not reproduce well in their own shade. As these trees grow old and die, shade-tolerant Beeches will replace them, and the area will again become a self-sustaining Beech forest.

The replacement of one woodland community by another is known as forest succession, where short-lived, sun-loving pioneer trees are succeeded by long-living, shade-tolerant species.

At this sign, the trail turns:

The smooth, grey-barked trees in the vicinity of this sign are American Beech (Fagus grandifolia). Of the local tree species, the Beech is best adapted to growing in moderately drained soil.

In order to establish farm fields, an early owner cleared most of the Beech woodland from the property in the mid-1800s. The farmer retained this particular stand of Beeches to serve as the farm woodlot where trees could be harvested continuously for lumber and fuel. Beech is excellent firewood because it splits easily and burns slowly.

Hogs were penned in this woodlot to allow the animals to eat their favorite food, beechnuts. Two triangular nuts are found in each spine-covered fruit that drops from the Beeches in autumn. Beechnuts are sweet and highly nutritious, comprised of about 20% protein and 20% oil.

During the warm months, the overhead canopy of Beech leaves intercepts the sun's rays and allows only small flecks of sunlight to reach the ground. Note that little vegetation survives in the heavy shade. The few forest floor plants that do grow here call attention to themselves in the spring when they flower prior to leaf emergence in the Beech canopy.

If you are here in the fall, you may notice bunches of what look like brown sticks growing on the ground in this Beech forest. These are Beechdrops (Epifagus virginiana). These plants do not photosynthesize, and so they are not green. Instead, they parasitize the roots of Beeches, deriving all their nutrition from the trees instead of from the sun and soil, like green plants.

This sign marks the end of the path.

Wetlands are unique and special ecosystems. They provide habitat for an extraordinary variety of biodiversity, and they also recharge groundwater, produce healthy fisheries, filter pollutants, and reduce flooding. They may be wet year-round, wet during certain seasons, or wet during part of the day.

Wetlands weren't always recognized as valuable. In fact, they were historically thought of as wasteland. For the last 200 years, they have been drained and filled for agricultural land and urban development. Over 116 million acres of wetlands in the United States have been lost. Thankfully, wetlands are now recognized as crucial natural resources, and they are protected under the Clean Water Act.

Scientists and policymakers have also recognized that we need to recover the wetland habitat that we have lost. In fact, federal agencies have been working with partners to achieve a net increase of 100,000 acres of wetlands per year. To do this, wetland recovery projects are taking place all across the country. Such projects may take on several forms:

All of these initiatives are challenging and require complex techniques and scientific knowledge. For many projects, changes in the hydrology (water flow), soils, and the biota (plants and animals) are necessary to create or restore a functioning wetland.

To perform a wetland project, the appropriate site must be identified. Here at the St. Anne Wetlands, the site conditions have produced excellent wetland soils, hydrology, and biota; however, there is still a lot of land here that isn't wet, and it offers an excellent opportunity for wetland creation. Using the existing wetlands as reference sites, we can determine what characteristics make for a successful wetland here. Then we can work to mimic these same characteristics in the dry areas. Using excavation and the placement of berms, water hydrology can be changed to retain more water. And then wetland plants can be transplanted into the new wet area. Over time, as the plants grow and the animals move in, such an area will begin to look more and more like the existing St. Anne Wetlands, and we'll have helped increase the wonderful benefits that wetlands provide.

Help us protect the trails, wildlife, and natural areas so everyone can enjoy them safely.